Lessons from René Girard Part II

6 More Things I've Learned from a Great Interdisciplinary Mind

This is the second part of a series on life lessons from René Girard. Part I (Lessons 1 - 6) is here.

Now, let’s pick up where we left off:

7. Look for the Mimesis in Current Events

René Girard was an avid consumer of the news. That might seem strange for someone keenly aware of mimetic phenomena. Wouldn’t the smart move be to tune out? To get one’s news from the server at the local diner? From someone who has already filtered through the noise?

Maybe. But temperance is a higher virtue than abstinence, and prudence is still more excellent.

In a world where consuming some amount of “news” is practically inescapable, I want to develop the ability to see behind the facade presented; to see the real forces at work; to read the signs of the times.

There is reading, and then there is reading.

Cynthia Haven, René Girard’s biographer (Evolution of Desire) observed this during her numerous living room conversations with him:

“His great serenity of spirit was marked by a passivity that puzzled me. I wondered, at the time, whether it was age, or the recognition of the futility of all oppositions, doubles, fighting, and rivalries.”

It could be that with age comes recognition—though we don’t need to have aged to recognize it.

Girard modeled an anti-mimetic, meditative approach to the news. When we learn of the Twitter Ban, for instance, the anti-mimetic response is not to debate what kinds of policies or language or personalities may or may not have led to the event—the reactionary taking-of-sides. Rather, the first step is sinking down into it and asking questions like:

What does this mean? What’s happening in the world? What are the mimetic forces at work here?

The specifics are always downstream from there.

8. Read Literature Through the Lens of Desire

While I was living in Rome, I met Matthew Luhn from Pixar Animation Studios, the lead “storyteller” for the films Toys, Up, and Inside Out.

When I asked him what the key to a good story is, he told me something I’ll never forget: focus on what each character really wants. And “Start with the things you are already watching and reading.”

I followed his advice. Whether I was reading Dostoevsky or Shakespeare or watching Breaking Bad, I noticed that all good stories take the desires of characters seriously. Good storytellers know that each character deeply wants something, and that his wants are affected by what the people around the character want.

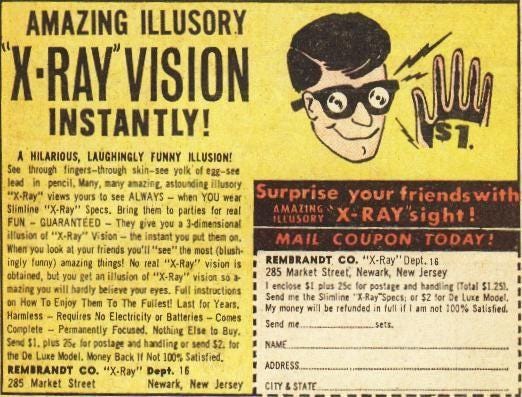

This exercise of reading with “X-Ray Vision,” it turns out, is how René Girard began to notice the role of mimetic desire in real life. He saw that the most compelling stories in history are so compelling precisely because they’re true. They’re true to human nature. The greatest of them all get mimetic desire right.

Classic and enduring stories like Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov are powerful because they are dripping with mimetic desire.

Don Quixote is sitting around reading books when the desire to be a knight captivates him. Until he started reading about heroic knights, the thought of being one had never even crossed his mind!

The lovers in A Midsummer Night’s Dream compete with one another not because they accidentally fell in love with the same woman; they desire the same woman because they imitate one another. Shakespeare comically underscores each lover’s romantic illusion that his is a “true love” while the audience is in on the game: they imitate one another’s desires and end up in an escalating mimetic rivalry.

In the Brothers Karamozov, Dostoevsky takes the reader through the entire process outlined in this book. Dostoevsky embodies in his characters his own evolution of desire. While two of the Karamozov brothers, Dmitri and Ivan, are consumed by mimetic desire just like their father, the youngest son, Alexei (Alyosha) is an “outsider” who lives (and eventually leads) others through desiring something that transcends the mimetic crisis that the rest of the characters are in.

These stories are powerful because we sense, whether consciously or unconsciously, that the characters are subject to the same forces that we are.

9. Discover New Layers of Meaning in the Bible

The Judeo-Christian scriptures are filled with mimesis. In Girard’s view, they reveal the mimetic nature of desire and the conflict and violence that often springs forth from it without our being aware of the origins.

Reading scripture through the anthropological lens of mimetic desire is an experience unlike any I’ve ever had. It opens up new perspectives.

Girard discusses numerous “mimetic readings” of scripture in his book I See Satan Fall Like Lightning. Cain and Abel is the story of sibling rivalry par excellence. Ask yourself: What were they competing for? What were Jacob and Esau competing for? What is the significance of the meaning of Jacob’s name?

Very early on in the book of Genesis, when the creation story is recounted, we see mimetic desire operative in the serpent who suggested a desire to Eve for the fruit of the forbidden tree; from there the desire spreads to Adam, to their children, and on through the generations of descendants, leading to envy and rivalry becoming a core part of the human condition.

To read a literary account of how this plays out in human life, I recommend John Steinbeck’s masterpiece East of Eden. It falls squarely in the top 10 most important works I’ve ever read in my life.

10. Romantic Lies, Romantic Love

Why do people play hard to get? Girard had one of his first insights into the nature of mimetic desire while he was a young student in France. He was in love with a young woman. They were dating—until she asked Girard to marry her. Taken aback at the forwardness and timing of the request, he quickly backed off. They went their separate ways.

But as soon as she accepted his decision and started dating other men, Girard was drawn back to her immediately with an inexplicable longing. The more she denied herself to him, the more he wanted her. “She influenced my desire by denying it,” he recalled.

The woman’s new suitors were new models of desire for Girard, modeling his ex-girlfriend desirability to him. Without them, his desire waned. With models, his desire was inflamed.

“I suddenly realized that she was both object and mediator to me,” he remembered. “Some kind of model!”

In other words, people can model desirability for themselves. And this provides one clue into the tried-and-true method of playing hard-to-get: it works because it affects our perception of someone’s desirability through the way that is modeled.

Human desire needs models to help guide the way—and those models double as obstacles, reinforcing our desire for something the more that they block the way. We are all, in some sense, obstacle addicts. If there is no obstacle to our desire then we often think that we have made the wrong choice.

And when it comes to Romantic or sexual relationships, that can lead to some very strange behavior—manifesting itself in one of its most extreme forms in the phenomenon of BDSM, in which the dominant and submissive roles reinforce and amplify the subject-model dynamic of desire to the point where it is fetishized. But I’ll have to save that discussion for another edition with some kind of NC17 disclaimer on it.

The life lesson here is simple: understand that you are likely attracted to people and things merely because you perceive them to be difficult or slightly out of reach. Such is the nature of mimetic desire and its quest for the perfect model.

You can read more about Romantic Lies, Romantic Love here.

11. The Meaning of Scandal

Models of desire are always scandals—literally, stumbling blocks—to those who don’t understand how the subject-model relationship works.

Models are obstacles that stand in the way of getting whatever it is we think we want. We convince ourselves that the other person has something that would make us happy—whether that’s wealth or a love interest or a job. This is the cause of endless misery for humans. We normally don’t even realize that we’re doing this, though.

We stay locked in cycles of competitive desires, a zero-sum game in which we believe in the primacy of our desires and view other people as encroaching on them—when in fact it’s probably other people who helped generate and form those desires in the first place!

Mimetic models need not be rivals—but the malignant forms of mimetic desire always make them so.

Girard wrote:

“Passive, submissive imitation does exist, but hatred of conformity and extreme individualism are no less imitative. Today they constitute a negative conformism that is more formidable than the positive version. More and more, it seems to me, modern individualism assumes the form of a desperate denial of the fact that, through mimetic desire, each of us seeks to impose his will upon his fellow man, whom he professes to love but more often despises.”

12. Hope: The Power of Positive Mimesis

We’re not condemned to negative or destructive cycles of mimetic desire—we’re not condemned to a kind of Eternal Return.

While it’s not possible to transcend mimetic desire (it’s simply part of what it means to be human), it is possible to transcend the mimetic impulses that lead to destructive conflict.

We’re free to choose to take anti-mimetic steps in our lives, to live in more anti-mimetic ways—to not become children of our age.

Things like empathy, forgiveness, heroic self-sacrifice and love are every bit as mimetic as rivalry—and even more so, because these are the things that call to mind the better angels of our nature, that remind us of our great dignity, our tremendous capacity for love—if only we’re exposed to the right models and allow them to thoroughly infect us.

In the 2020-2021 year of the pandemic, one of the great tragedies is that the word “contagion” has taken on an extremely negative connotation. It’s easy to forget that there are some things worth getting infected by, and some things worth making contagious.

Hopefully we haven’t spent so much time erecting barriers for the bad that we accidentally erected them for the good.

We’ll have to shatter our defense mechanisms where necessary.