12 Life Lessons from One of the Most Penetrating Minds in History

René Girard's genius was directed to human nature, not math. His insights are no less important than Einstein's.

René Girard (1923-2015), the great Stanford professor known by some as the mentor to Peter Thiel, called “the Darwin of the social sciences” and the “Father of the Like button”, was a genius of a different order. He made visible what is normally invisible: the delicate dance of desire that human beings play from the moment they’re born, and which explains some of humanity’s more “irrational” behavior.

As we’ll see, it’s not irrational; it’s mimetic. Because pundits on CNBC don’t understand the mimetic impulse in human beings, they scratch their heads when there’s an inexplicable parabolic rise in a stock or when GameStop investors and hedge funds battle it out in the market with no regard for the underlying fundamentals of a company. The media seems perplexed when Republicans and Democrats are locked in stalemate politics and ignore obvious priorities or wins because the desire to punish their opponents is greater.

Girard’s ideas also explain why we’ll never “fix” the so-called Cancel Culture with some kind of artificial ceasefire because it would ignore the fundamental and perennial desire of human communities to purge themselves of perceived threats to their stable order. (Even when the order being preserved is violent, and it always is.)

The first words out of Girard’s mouth in one of the courses that he taught early in his early at SUNY Buffalo were:

“Human beings fight not because they are different, but because they are the same, and in their attempts to distinguish themselves have made themselves into enemy twins, human doubles in reciprocal violence.”

A far cry from the typical sleepy-eyed “Welcome to the class. Now, let’s go over the syllabus.”

Girard was interested in the most fundamental questions that plague humanity, and he applied his brilliant mind to them with great intensity while leaving out most concessions to his readers.

I am reminded of how Satoshi Nakamoto responded to a question about his nascent crypto project: “If you don't believe it or don't get it, I don't have the time to try to convince you, sorry.”

Girard was a hedgehog with one big—one massive—idea: mimetic desire. Its discovery changed his life forever in the fall of 1958.

Have you ever had an important insight come to you in the nature of a gift? Not as the result of a conclusion, as if you’d reached the end of a long math problem, but as the experience of a revelation? That seems to be the way that Girard experienced his initial insight into mimetic desire as he was working on the last chapter of his book, Deceit, Desire, and the Novel.

It happened to him as he was on a trundling train from Baltimore to Bryn Mawr to teach a class.

“I was thinking about the analogies between religious experience and the experience of a novelist who discovers that he’s been consistently lying, lying for the benefit of his Ego, which in fact is made up of nothing but a thousand lies that have accumulated over a long period, sometimes built up over an entire lifetime.”

(From Cynthia Haven’s excellent biography of Girard, Evolution of Desire.)

“Everything came to me once,” he recalled. “I felt that there was a sort of mass that I’ve penetrated into little by little. Everything was there at the beginning, all together. That’s why I don’t have any doubts. There’s no ‘Girardian system.’ I’m teasing out a single, extremely dense insight.”

So let’s tease it out a little. Here are some of the implications of that insight, starting with the core one.

1. Mimetic Desire Governs the World

“Mimetic desire is an absolute monarch,” Girard wrote.

It is the “thing hidden since the foundation of the world”, to borrow the words of Girard’s magnum opus (Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World). Girard, in turn, took them from the gospel of Matthew.

“I will open My mouth in parables; I will utter things hidden since the foundation of the world.” (Matthew 13:35)

Bold. Comparing yourself to Jesus?

That’s not what Girard was doing, though. He saw his work as a working out of the core anthropological truths about human relations that were already present in the gospel text—nothing more.

In other words, Girard didn’t view himself as having had some “new” idea. He saw himself as having seen something in the historical unfolding of the Judeo-Christian scriptures (not just the texts themselves, but also the events that the words gave meaning to) that others failed to fully grasp.

And that thing was mimetic desire.

It was present at the dawn of humanity. The mythological language in the Book of Genesis tells us of something important about desire in the story of Eve and the Serpent. It’s often overlooked.

Eve desired to eat the fruit of the forbidden tree only after the desire to do was suggested to her—in other words, modeled to her—by the serpent.

It was the first instance of what we might call deviated desire. Eve’s desires were hijacked, taken off track, by the desire for the fruit. She never would have desired it had the desire not been modeled to her by the Serpent.

Suddenly, a new desire was kindled inside of her for something that she believed would give her a special power—the knowledge of good and evil—but which instead blinded her to the truth of her own desires and caused them to become disordered. As the scriptures tell the story, these disordered desires immediately began to be passed down to her children and their children and to the rest of humanity.

It was as if the compass of her desire was placed near a magnetic object that threw off its internal mechanisms and caused it to read a false north. (For those who don’t know how to use a compass: it must be flat and away from any objects that can pull its highly sensitive needle from reading the earth’s natural magnetic fields.)

Life is a process of declutting our desires; of bringing order to our disordered wants.

If the world is disordered and chaotic, it’s because our desires were first. The world, and our future, is simply a reflection of what we want. And if what we want most is to destroy one another, that’s what we’ll do.

Mimetic desire is a constant presence across politics, business, relationships, work, play, even the books we choose to read. It’s at the heart of human relations.

We don’t understand ourselves until we understand our desires.

2. The Power of Fresh Eyes

Girard’s discovery of mimetic desire came while he was reading classical literature.

Girard’s PhD was in history. But he was an auto-didact with broad interests and enormous range—something rarely seen today, when hyper-specialization is the norm.

Girard read and absorbed philosophy, sociology, theology, literary criticism, evolutionary biology, and more. When I met with Dr. Andrew Meltzoff, one of the world’s leading brain science and childhood development specialists, he recounted a meeting with Girard in Palo Alto in which the great professor was enthralled by the neuroscience of mirror neurons. He was always looking to make new connections.

Girard was able to see things with fresh eyes in fields that were completely unfamiliar to him—not believing the lie that only the experts or those with great familiarity know best.

There is great precedent for innovation coming from people who stand at a greater distance from the thing being looked at. Henry Ford “saw” what would become the assembly line in a slaughterhouse as cows were broken up into their component parts and processed. Daniel Kahneman shaped the field of economics as a psychologist because he saw behavioral phenomena in economic processes that economists were too in the weeds to notice.

In Girard’s case, it happened in literature. Early in his academic career in the U.S., he was asked to teach literature courses about books that he hadn’t yet read. He was reluctant to turn down work, so he took the job on. He found himself staying just one step ahead of his students in working his way through classic novels: Standhal, Flaubert, Dostoyevsky, Proust, and more.

With his lack of formal training and the need to read quickly, he started to look for patterns in the text. In doing so, he uncovered something that all of the literary critics had missed: characters in the novels never desire anything spontaneously; their desires are shaped in and through their relationships with other characters who act as models of desire for them.

This discovery was like the Newtonian revolution in physics in which the forces governing the movement of objects can only be understood in a relational context—not independently.

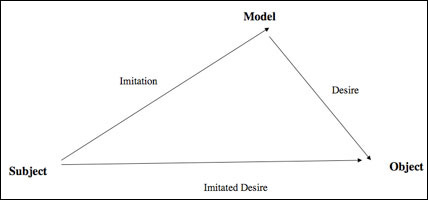

He never would’ve been able to see this had he been infected with the intellectual fashions of the time. They would have clouded his vision and prevented him from being able to see the truth that he called, at the time, “triangular desire”, but which eventually came to be known as mimetic, or imitative, desire.

[Above: triangular desire. I dislike these images because they remind me of trigonometry class so I we-worked them for the book. But it is helpful for illustration the fundamental idea. What’s missing from this image is the sequence with which the movement happens. It’s this: 1) Model desires object 2) Subject imitates model; 3) Subject imitates the desire and believes their “imitated desire” (at bottom) is entirely their own]The lesson? Don’t assume that just because you don’t have technical expertise in something—whether it is coding websites or looking at history or looking at societal phenomena surrounding the Covid-10 pandemic—that you can’t see things for what they are and uncover truths that others may not be able to see due to whatever psychological, intellectual, emotional, or spiritual blocks are preventing them from doing so.

3. We’re Killers Who Absolve Ourselves from Our Crimes

The dark secret that Girard discovered in human history is that violence is at the foundation of human culture. Institutions, taboos, prohibitions—indeed all culture—has developed in response to violence (what Girard calls “Founding Murders”) and to mitigate that violence.

Humans continually turn to the scapegoat mechanism to resolve societal threats.

When people in a community are engaged in contagious conflict that is on the verge of becoming a war of All-Against-All, Girard found that they suddenly unite against a single victim that they believe is the cause of their disorder. They believe that if they purge this person (or group) from their midst, they will purify themselves from whatever it was that plagued them.

The holocaust looms largest and most horrific in the twentieth century. In a way, it is the most extreme example of what happens on a much smaller scale—even on the level of a friend group or family or company—on a daily basis. The transference of blame for purposes of purification seems to be a perennial feature of human behavior.

The scapegoat mechanism was, in some sense, a “social innovation” that saved communities from their own violence by directing it in a very targeted way toward one person. Kill one cell; preserve the whole body.

The high priest of Israel at the time of Jesus knew how this process works. “You do not realize that it is better for you that one man die for the people than that the whole nation perish,” he said. He knew that without a properly sacrificed scapegoat, the whole nation would collapse.

We are totally blind to our own violence and our own role in this scapegoating process because we are caught up mimetically in the violent contagion that spreads from person to person. Many things are mimetic; aggression is one of the most.

This is one of the “things hidden since the foundation of the world” that Girard explains in his magnum opus: humanity constantly covers up its violence through myths that reframe the violence in a way that justifies it.

Plato wrote that if there were ever a perfectly just man in the world that he would surely be murdered. If you believe the Christian scriptures, this is precisely what happened. (This is why Girard thought that they have a fundamentally revelatory function; not just revealing God to humanity, but revealing the nature of humanity to ourselves in a way that would’ve been impossible to see without the scapegoat mechanism being exposed in the scriptures; that exposure reaching its culmination in the crucifixion in which everyone could see that an innocent victim had been sacrificed out of self-preservation.)

If you don’t, then you might still be able to look at the gross injustice in the world and see that there’s a violent and self-justifying impulse at the heart of human behavior in certain circumstances. Nobody who commits violence seems to truly believe that their violence is unjust. It’s also “good” violence; the Other’s violence is always “bad.” All violence is bad. That much should be clear. But Americans spent the vast majority of 2020 justifying various forms of violence, whether from police or from rioters.

The mistake is to think that only others—and not ourselves—are capable of participating in this mechanism. We may not inflict violence in exactly the same way that others have, but we are capable of inflicting it in our own ingenious and egregious ways. And it’s precisely our refusal to accept the truth of this that ensures that the cycles of violence in human societies will continue.

The Judeo-Christian tradition calls this propensity of humans to commit violence against the moral good—violence against other people—sin. And the extent to which we commit sins is often in direct proportion to the extent to which we believe we are free from the possibility of committing them.

The accelerating desire for metaphysical purity in a world in which there is none can only result in violence or acceptance. The more zealous we are to rid the world and other people of their faults and failings, the less zealous we are to rid ourselves of them.

The lesson of Girard’s insight into violence—at least the one that I carry with me—is that it’s impossible to rid the world of bad people or bad ideas or opinions that I don’t like. It’s also impossible to become too aware of my own weakness and tendency toward self-justification. Perhaps if each of us renouncing our worst mimetic behavior, we might spread a different kind of positive contagion based on recognizing the inherent dignity of every human person.

Flannery O’Connor took a dimmer view. “The violent bear it away,” she wrote. They always have.

4. Humans Are Deeply Religious Creatures

If you sense that there might be a religious dimension to the Bitcoin mania, then you haven’t yet lost your sense of smell.

The market economy is a sacred institution. All institutions are.

We’re fundamentally religious creatures in Girard’s view. Sacred rites and rituals have been a part of humanity for millennia, and it would be ignorant to assume that our supposed rationalism has freed us from thousands of years of religious formation that so thoroughly imbues our culture.

There’s strong evidence that systems of exchange were developed in the context of religious rites. All of the earliest coins have been found around sacrificial temples. Thousands have been found around the temple of Juno Moneta (notice some relation to the word money)—a temple in which coins were known to be minted.

Why was money so integral to the sacrificial rite? Because people needed animals to fulfill the sacrificial rite; money was essential to make the exchange.

The real powers and principalities in the world are not the traditional heads of state, but the mimetic processes that develop independently from them. Power structures can shift overnight. Girard notes, with his usual penetrating insight, a situation that occurred in 17th century France that makes it hard not to call to mind the current crypto movement that is ushering in a new economy:

When Louis XIV ran out of money, he was forced to invite a Jewish financier to Versailles. The King had to court him because he needed money! He could not simply take it without violating certain rules, which could not be disregarded with impunity. Therefore, in spite of his tremendous power, Louis XIV was already the prisoner of an economic system that was evolving independently from absolute monarchy.

Remember, mimetic desire is the absolute monarch. But what are people looking for as they find new models to imitate? What is the driving force behind our never-satisfied striving?

All desire is a desire for being, according to Girard. In other words, everything we want is really our way of trying to be a certain way—to be a certain person. It’s our awareness of our many limitations (recognized or unrecognized) that leads us to search for models to imitate or emulate, for new goals to pursue, for new places to travel, new people to meet. Desire is about our search for transcendence.

Desire, according to René Girard, is always for something we think we lack—or else it wouldn’t be desire at all. His main discovery is that desire is not object-oriented, as we commonly assume; it is the search for being itself.

There is literally no object or achievement or person in the world that would ever satiate our desire. This is why desire always has a fundamentally religious character. It’s when we don’t recognize our own religiosity that we start to seek fulfillment in stranger and stanger places.

5. The False Allure of Competition and Rivalry

Competition is different from rivalry.

The idea of competition is abstract, illusory, precept enshrined once and for all in neoclassical economics as one of our greatest goods.

But listen to what Peter Thiel has to say about competition in his eminently Girardian book, Zero to One:

More than anything else, competition is an ideology—the ideology—that pervades our society and distorts our thinking. We preach competition, internalize its necessity, and enact its commandments; and as a result, we trap ourselves within it—even though the more we compete, the less we gain.

The cult of competition so engrained in the American mind that it leads us to believe that something is only valuable if people are fighting for it. We learn in school that competition is what spurs creativity, keeps prices down, and leads to an “efficient” market. We’re indoctrinated with these ideas as part of our economics 101 classes.

Yet competition is a strange thing to desire if you stop and think about it. Why would we choose to have competitors if given the choice to not have competitors?

We carry over some of our unquestioned assumptions about competition to all other domains of life. Competitive colleges must be better than colleges that are easier to get into; men and women with more suitors must be more desirable; restaurants with longer lines must have better food. These things are the result of mimetic desire creating false scarcity.

A moment’s reflection reveals the folly of these assumptions. We all know that competition for something drives up prices, but not necessarily the quality of the product. Take university education, for example. Despite the mimetic run-up in enrollment and tuition, there is little evidence that students are getting a better education today than they were 30 years ago (some would argue it’s far worse); yet, tuition has increases have outpaced inflation more than 2:1.

Girard realized that most competition is unnecessary because it’s the product of mimetic desire—people converge on one object and then reinforce one another’s desire for that object in a way that quickly becomes detached from the object itself. The model is what is valuable; not the thing itself.

Girard’s insight into mimetic desire had the second-order effect of explaining rivalry. Because people come to want the things that other people want—because desire is imitative—people naturally fall into rivalrous competition with other people. If given enough time, human relationships tend toward conflict as we view other people as scandals as threats to our pursuit of fulfillment—a pursuit that is itself conditioned by what those other people want.

And that will perhaps allow us to see the wisdom and necessity of the 10th commandment, which (strangely) prohibits rivalrous desire:

You shall not covet the house of your neighbor. You shall not covet the wife of your neighbor, nor his male of female slave, nor his ox or his ass, nor anything that belong to him. (Exod. 20:17)

From the earliest writings of the biblical tradition, the tendency of humans to covet their neighbors good is recognized and prohibited. There would be no need to prohibit it if it weren’t a foundational part of the human condition.

It is a tremendous step in the maturation of an individual to realize their own rivalrous tendencies. It’s the first step toward freeing ourselves from their more destructive consequences.

But few do this. Girard notes why:

If individuals are naturally inclined to desire what their neighbors possess, or to desire what their neighbors even simply desire, this means that rivalry exists at the very heart of human social relations. This rivalry, if not thwarted, would permanently endanger the harmony and even the survival of all human communities. Rivalistic desires are all the more overwhelming since they reinforce one another. The principle of reciprocal escalation and one-upmanship governs this type of conflict. This phenomenon is so common, so well known to us, and so contrary to our concept of ourselves, thus so humiliating, that we prefer to remove it from consciousness and act as if it did not exist.

We have to recognize it and address it.

Empathy is one of the primary keys to breaking out of our cycles of destructive rivalry. Why? Because the very nature of empathy is entering into another’s experience without necessarily identifying with it completely or even agreeing with them. It involves entering into the mind and experience of another while maintaining our self-possession.

Developing this skill allows us to enter into relationships with people and groups that don’t put us at so much risk of getting caught up in the disemmbling fog of crowds and mobs, or mimetically adopting other peoples’ opinions and desires as our own while keeping up the conceit and affectation of self-sufficiency.

6. The Identity Flippening(s)

My friend Jack Butcher of Visualize Value published this excellent piece. He wrote:

What is difficult to plot on a chart is the proportion in which our identities are shifting from offline-first to online-first.

Physical status symbols are of no utility if you aren't going outside.

If the internet is where you get your culture and build your relationships, it's also where you signal your status.

I don’t think anyone really understands what this new world of online identity-formation is doing to the process of people coming to know who they are.

Girard took a view of identity that is highly relational. We are, in a sense, constituted by our relationships: with our parents, with our siblings, with our friends. These relationships form part of how we understand the Self.

Perhaps nobody explains who we think we are more than the models we aspire to be. We are not yet who we ultimately think we should be. (Except perhaps an absolute narcissist, who is so insecure that he has to walk around convincing himself that he fits an idealized image of himself—that idealized image of himself is the model of desire that he aspires to; the tragedy is that it doesn’t exist.)

We are not yet who we believe we should be, so we unconsciously form our identities in relation to various models of desire.

The challenge is that today we have more models than ever before to choose from, and the models are more ethereal than ever. They may even be pseudo-anonymous personas who we are simply projecting ideas onto. Do we even know anything about the thousands of people we “follow” on social media other than what little we can read into their cryptic tweets and poasts?

It is shocking how little we know them. Yet we’ve thrown 10 to 14-year-old children into this world where they are surrounded by tens of thousands, even millions, of models of desire, at the most critical stage in their process of understanding who they are.

All Girard’s work on mimetic desire, rivalry, and scapegoating ultimately comes down to the question of identity. Who are we? That question is more tied up with the question of "What do we want?” than we realize.

We are, in some sense, what we desire. At the end of our lives, we will have spent most of our time and energy pursuing the things that we wanted the most—whether those things are drugs, alcohol, money, relationships, food, service, work, family, writing, or the pursuit of what we believe is our vocation.

The will does it wants. And that’s why it’s all-important to shape our desires—to assume some agency and intentionality in this process.

Our desires are ultimately the greatest predictor of what we’ll do.

Show me a man who renounced his greatest vice and has learned to love, and I’ll show you a man who wanted to. And that’s because someone else had provided a powerful enough model of desire.

We all need models of desire. The question is where will we find them. In each other?

That’s the great drama of human relationships. Each of is at every moment of the day helping one another want more or want less. There’s no in-between.

The 6 additional lessons are for premium subscribers to this newsletter.

A former friend and colleague roel kaptein was a friend of girard-we worked on these practical mimetic understandings since 1979 within the Corrymeela Community

Your exploration of mimetic desire in the web influences on identity and young people is a new frontier-well done