Ozymandias: Breaking Bad Mimesis

How much Value can one person Add before they get to the center of a soul?

This is part of the story behind the story found in the introduction to my book, Wanting. I’ve never told this part before.

My story was sad. But like anyone addicted to Hustle Porn and hustle culture, I didn’t believe in sad stories—let alone my own. Like most entrepreneurs, I was extraordinarily good at lying to myself, at creating a carefully curated presentation of my self in the world (‘self’ with a lowercase ‘s’, because I was not a real Self at that point). Social media before social media.

I found that when entrepreneurs did share stories of adversity or failure, they inevitably included a “but then…”

The moment of triumph.

And they always fit an archetypical narrative arc so perfectly that at some point I realized something was off. My story and my experience was simply not tracking.

Either their stories were true and unrecognizable to me because I was on a different track; or their stories were not the real stories. There was the possibility that my experience was real, but nobody had the balls, or self-awareness, or time to tell their own. A lonely place.

I suspected this strange phenomenon extended way beyond the startup world and into workplaces everywhere. Perhaps the gradually recognition of the mimetic traps is partly behind the so-called ‘Great Resignation.’ It’s worth asking, though: what are people resigning from? It is really a job? Or is it the pursuit of an unfulfilled desire that has finally been exposed as shallow and thin?

Back to the early 2000’s: I was on a hyper-mimetic track in college. I graduated from NYU Stern (I fought ridiculously hard to be near the top of my class, even with the infamous ‘Stern curve’—the most mimetic grading system known to man), worked on Wall Street (and for a small private equity shop for a short period of time), and finally made my way to California where I sank my end-of-year bonus—and eventually about $150,000 in credit card debt, too (yes, they gave me that much)—into my first startup.

Fast forward about six years. Even after having had success, I was miserable. I hadn’t been able to cultivate anything even remotely resembling a healthy relationship. When I wasn’t working, I was in the gym blasting EDM directly into my eardrums and texting clients, partners, and vendors between sets.

I knew—at least in those rare moments when I was honest with myself—that I had a hole in my soul. I also knew that listening to podcasts on stoicism, going to yoga, or making a pilgrimage to look at an effigy of a burning man in the desert weren’t going to save me. Around that same time, a bunch of friends were running the Las Vegas Rock’n’Roll Marathon (I was living in Henderson, NV, by this point), but I couldn’t help but thinking: ‘What are they running from?).

One night I was in a casino with the late Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh, who was a heavy smoker. He planned to run the marathon that year. He told me that he followed a program that he found online where you could go from being almost completely sedentary (and smoking) to running a full marathon in just 3 months of preparation, as long as you follow the prescription exactly. “It’s science,” he told me as he took a drag from his cig that night in the casino. He was starting the program the next day. “You should do it.”

“No thanks,” I replied. Although I couldn’t articulate it at the time, I felt like any physical pain that I would’ve endured preparing to run the marathon would’ve been a poor substitute for the spiritual pain that I needed to endure in order to come to grips with my many faults and failings.

I woke up the next morning with a burning desire to go to confession with a priest. I was raised Catholic, but I hadn’t been to church in a very long time—and I hadn’t confessed my sins to a priest since I was about nine years old, at St. Andrew’s Elementary school in downtown Grand Rapids, MI. (And c’mon, does that even count? I think I may have been mean to a cat or something at that point.).

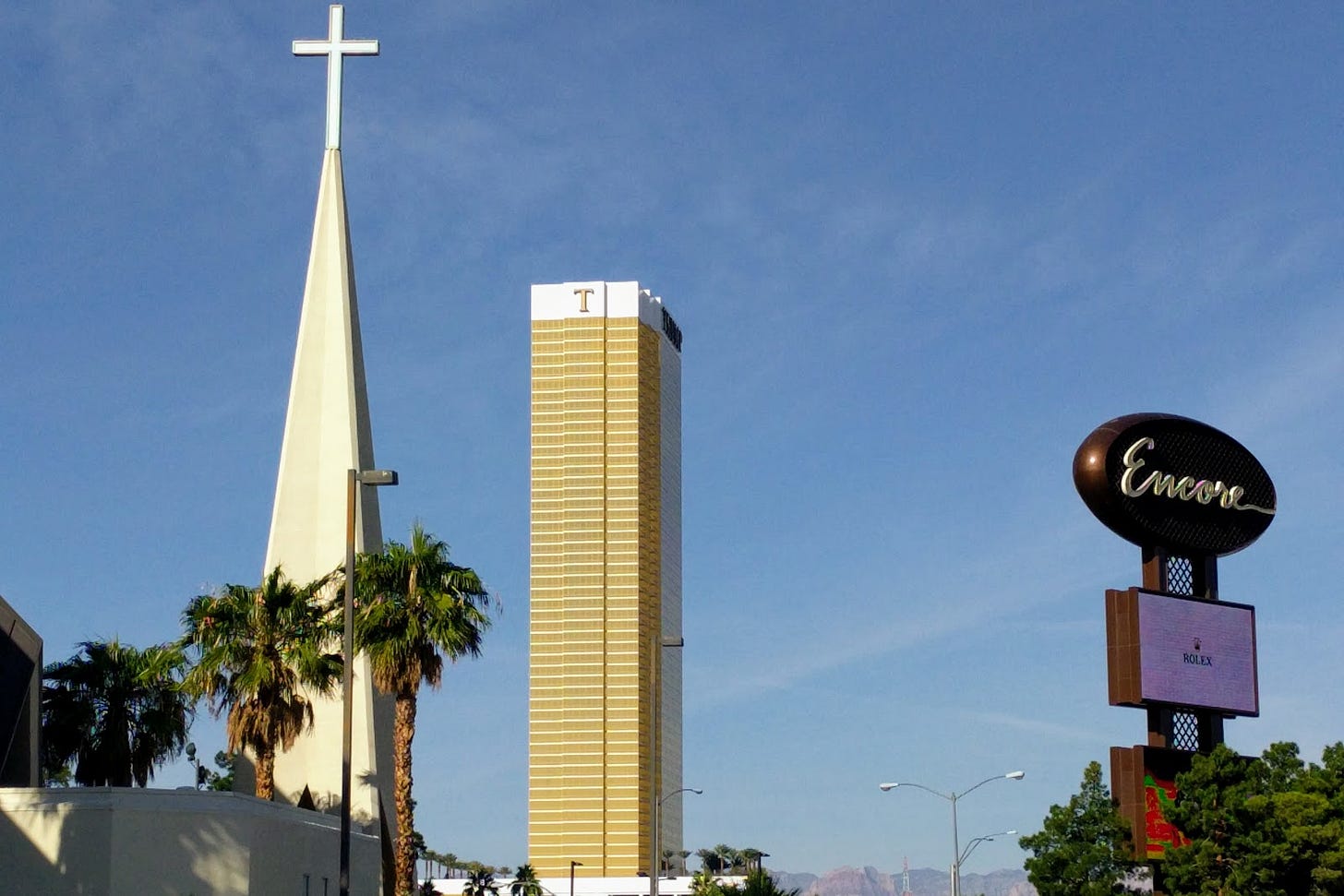

So I made my way to the Guardian Angel Cathedral on the Las Vegas strip—literally right next to the Wynn Casino where I’d gotten wasted the night before.

I poured out everything I could remember to this poor priest during the general confession time (open to the public) prior to the noon mass. I was in there for about 15 minutes, holding up the massive line behind me (who knew? there is demand for forgiveness in Vegas…). When I was done, the priest asked me to sit in silence in the church for 10 minutes and to consider doing something ‘generous’ for the poor (likely because part of what I had confessed to him was the squandering of my money on frivolous and selfish things).

I think that when you have multiple bank accounts with a certain number of digits in them, various outstanding debts, and the ability to win (or lose) large six-figure contracts overnight, money becomes something very abstract, and there is a strong temptation toward financial nihilism—in other words, a way of thinking that making and losing a lot of money is easy and relatively untethered to any form of real ‘value creation’, and that ‘nothing really matters, certainly not this bottle of Greygoose I’m about to buy for $500—it’s just money.’

I did my time in penance and dropped whatever cash I had on me in the ‘Poor Box’ on my way out of the Church, and I left feeling an extreme sense of understated peace. There were no tears, no heart-wrenching agony. No montage music started playing as I walked to the car. But I drove home knowing that something important had happened, and I’d just experienced the most radical honesty and vulnerability and mercy of my life.

‘Mercy’ was word was on my mind for the rest of the day and the week. What role does mercy have in business, if any? How I live a less transactional life? What does it mean to build a company and create a company culture that rewards acts of heartbreaking love just as much as and maybe more than works of staggering genius?

I had no answers, but I distinctly felt like I needed a re-eduction in what it means to be human.

So much of my humanity had been stripped from me. In the tireless effort to ‘grow’ my businesses, there was little energy left for personal growth. My humanity had been stripped from me because I had stripped it from myself; it was the same baneful wear and tear that makes med school students begin to start walking out in public in sweatpants having not showered for three days, so focused as they are on studying, and which makes it hard to look at a person and not see merely a body. Market forces, in their own way, have a way of making us lose sight of the person at the heart of the market.

What is it that you are studying, Luke, by running yourself into the ground like this? Markets? Politics? ‘Business’? ‘Success’? And to what end? All of these things came down, I thought, to the study of desire. Markets are simply a reflection of what people want; how people vote is an indication of what people want or don’t want. And success in business has come to be thought of as Adding Value™—yet what kind of value? That, too, has everything to do with desire.

This phrase Adding Value™ seems to mean the value that one places on unfulfilled desires, so you ‘add value’ whenever you help someone fulfill a desire whether it is leading them to fulfillment or misery. In the horizontal exchange of value, each party subjectively fulfills a desire which they value, on the margin, more than the other party.

If you take it far enough, ‘Adding value’ usually means nothing more than ‘adding desires.’ That is why, as Adam Curtis terms it, the economy became one giant Happiness Machine beginning in the early 20th century.

(In the video below, you’ll learn all about Eddie Bernay’s and his Torches of Freedom stunt, which I mention in the first chapter of Wanting. Some great video footage of the man…)

The idea of ‘value’ seemed to me to be one of the most convoluted and confusing words in the English language. Does anyone actually knows what it means? Doesn’t seem like it.

I made it through four years of undergrad business school getting asked questions like ‘What’s your ‘value proposition’? without anyone ever stopping to seriously explain what the fuck value really means. It is understood vaguely, at most. I believe in values and in ‘value’, don’t get me wrong, but it is curious how this word and the idea it represents has taken on mythic proportions.