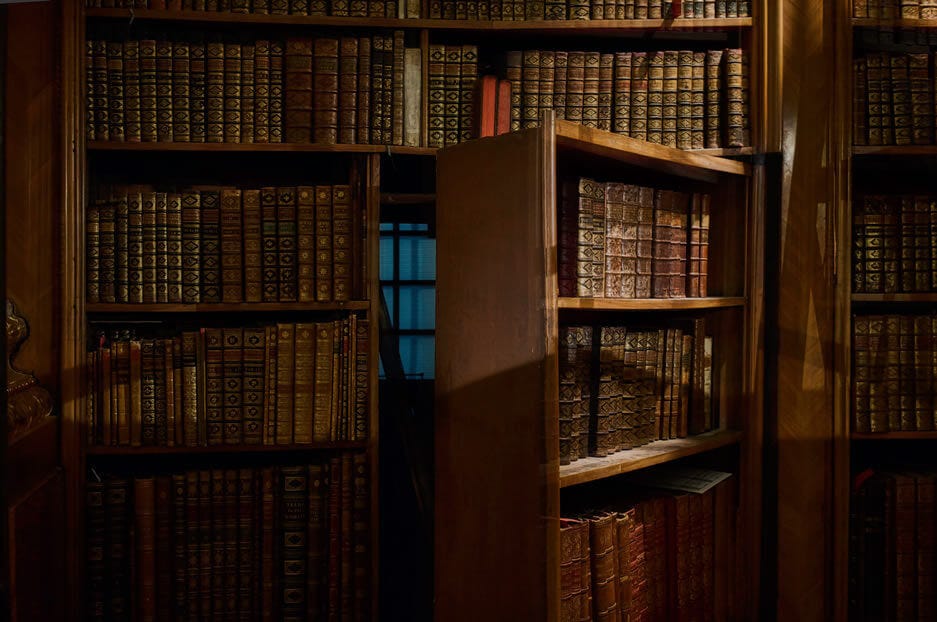

Deep Bookshelf 2021

The 10 books I read this year not because I thought I'd like them, but because I thought I wouldn't.

What we need are books that hit us like a most painful misfortune, like the death of someone we loved more than we love ourselves, that make us feel as though we had been banished to the woods, far from any human presence, like suicide. A book must be the ax for the frozen sea within us. - Franz Kafka

How do you choose which books to read?

In my early twenties, I defaulted into books—I read the easy stuff that came to me naturally.

All of us default into things—career choices, relationships, diets—without exercising personal intentionality. That intentional choosing is an important skill to develop in life, but it’s not easy. Books are an easy place to start, though.

When I say that “I read the easy stuff”, I don’t mean page-turners or Dan Brownesque thrillers; and I don’t mean the books that make the bestseller lists or a celebrity author’s ‘Book Picks of the Year.’

(I learned how most ‘top lists’ work over the past year, and Good God, it’s depressing.)

I’m also not referring to the eas…